Is there a person who, whenever they appear in your support queue, you audibly groan?

Working with difficult customers is one of the most challenging aspects of support work. What do you do when one of these customers steps over the line, from difficult to straight-up abusive?

Cutting abusive customers loose

At Raven Tools, we had a longtime customer who set up camp on the line between difficult and abusive. Let’s call him “Dwight.”

Dwight had been subscribing, off and on, for as long as I had been on the team — at least five years. He was always difficult to work with — unhelpful, passive-aggressive, generally contemptuous of having to contact support. And he’d send us messages like this:

Tell me, what am i actually paying for!! At least your company is consistent in it’s failures to provide anything close to acceptable levels of service!

Ouch.

Most of our users contact us only a handful of times. Dwight initiated more than a hundred conversations by himself. Gradually, the tone of these conversations started to slip into territory that was less passive and more aggressive. He started issuing threats — threats to initiate chargebacks for fraud, threats to contact our leadership team to have members of support disciplined for not getting his way, and so on.

This isn’t acceptable behavior. But what can you do about it?

When to fire a customer

The cornerstone of working with customers in a consumerist culture is “the customer is always right.” This usually translates into letting the customer talk at you until they’re satisfied or give up. Anyone who’s ever worked in retail probably has a story about a time when the customer was wrong, but they had no recourse. That doesn’t need to be the case in customer support.

You don’t need to accept abuse as part of the job.

If things are getting as bad as they were with Dwight, you should have the tools you need to do your job without worry. We decided that enough was enough, and we couldn’t support Dwight anymore.

3 steps to breaking up with a customer

Deciding to end your relationship with a customer isn’t like a bouncer kicking an unruly drunk person out of a nightclub. It’s more like you’re firing someone, which means that you have a high bar to pass before you can consider telling someone to stop using your product or service. It means you need to set up a framework.

You need a cause and support from leadership before you can confront the customer.

Step 1: Establish cause

Before Dwight, we had never explicitly asked a customer to leave. That means we needed to figure out what was important to us and draw a line in the sand. It should be hard to cross that line. You need to be able to distinguish between someone having a bad day and someone with a history of bad behavior.

We kept our standards for when to fire a customer simple:

Any form of racist, sexist, or harassing language. Simply put, you should never feel unsafe at your job. End of story.

Threats, either personal or professional. That includes threatening to initiate undue chargebacks with their credit card processor, threatening to expose information about the support agent, emotional blackmail, and so on.

A history of bad behavior with no sign of improvement or change.

That’s what we came up with, but every company and culture is different. The main point is that you need to create a standard and stick to it. Publish it as part of your customer interaction policy. Put it in your terms of service. Do whatever you can to codify that standard, to make it the law of your land.

Creating a standard and sticking to it requires support from leadership, which is the second step in the process.

Step 2: Get support from leadership

We needed to justify our conclusion — that Dwight had become too toxic to support — to the founders of the company.

How you eventually frame your argument depends on your management and company culture. You need to be prepared for leadership to ask, “Why is this a problem? Isn’t it your job to deal with people like this?” Framing the argument as a personal problem isn’t going to fly. Think beyond how this affects you and your team and present it as the business problem it is — not just for your teammates, but for your other customers.

We did that by gathering evidence to demonstrate a pattern of behavior — not just in conversations, but also social media posts and any other communication he lobbed in our direction. We sought to paint a picture of Dwight’s actions: that he was single-handedly making the entire team miserable. His conversations would get passed around like a hot potato because he would become unresponsive to one agent, forcing another to step in. More than that, the interactions were constant.

One mental hurdle you may need to summit is the potential of losing money by walking away from a customer. Think about it this way: One extremely high-maintenance customer eats up valuable resources, pushing your team toward burnout.

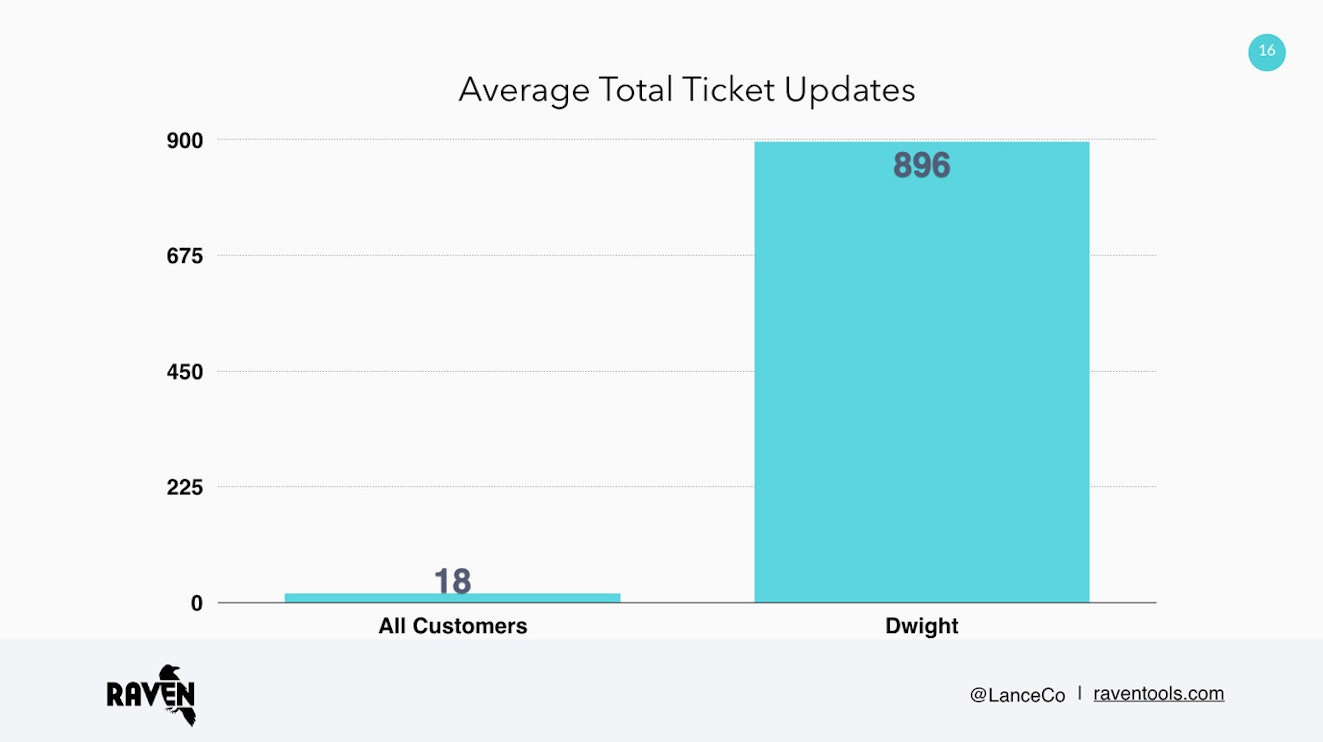

It also means your other customers aren’t getting the help they need as quickly or as satisfactorily as they deserve. For us, the average customer represents somewhere in the area of 18 interactions with support. Dwight had nearly 900. He was the fourth most prolific emailer in our company’s support history.

Better support for your overall customer base encourages customer retention. You’ll wind up making more money in the long run because your support team won’t be dealing with unnecessary strife.

This can be a challenging talk to have. Be prepared. Gather every scrap of information you can to make your argument, and use your data. Your goal is to make the answer obvious for whoever needs to sign off on your plan.

Step 3: Have the talk

After you’ve identified an abusive customer, brought the issue to the leadership team, and been given the green light, you have to confront the customer. All the work you did in gathering evidence will come in handy here.

The best approach is to give it to ’em straight. Be direct; don’t back down. Confrontation can be tricky, but remember, you’ve already done a lot of the hard part. Just present your evidence directly and with authority.

With Dwight, we laid it out as matter-of-factly as we possibly could. Our COO sent the email to give the message extra authority, and we quoted incidents directly back at him. We calmly explained why we were making this decision, wished him luck, and — this is important — refunded him six months of payments.

Why did we refund him? Because giving the outgoing customer something to part with defuses the situation. It makes it a business deal, not a personal offense. We didn’t ask if he wanted the refund, we just gave it to him, said goodbye, and moved on. In the end, he thanked us and we haven’t heard from him since.

Breaking up is hard to do

We’ve done this a few times since Dwight, and each time was challenging in its own right. Some have gone smoothly, like our interaction with Dwight. Others, like a customer who managed to issue threats while also attempting to promote his illegal business through our platform, didn’t.

In situations where the customer doesn’t accept their fate and move on, all you can do is be calm, present the information clearly, and be firm on your decision. When you codify what it means to cross the line, abusers can wail and thrash all they want, but you have a reasonable policy on your side.

Confronting and firing an abusive customer is challenging. But once you’ve established a framework for how to move through that process, it gets easier. Your team will become better for it — not just because of the drop in those audible sighs, but because they’ll have the comfort in knowing that there are options other than enduring abuse.