It's really hard to design products by focus groups. A lot of times, people don't know what they want until you show it to them.

— Steve Jobs

This quote became legendary as one of the most famous opinions from a highly opinionated man. Regardless of your personal opinion on this statement, it is remembered by so many because of the bold implications that Jobs makes about customer feedback.

Forbes called the quote ”a dangerous lesson.“ Even as someone who has presented ample research that customers can and do inspire innovation across multiple industries, I’m here to tell you that I sometimes agree with Steve Jobs’ sentiments.

Today we are going to look at a few split opinions on the sentiment of Jobs' quote, comparing the merits of focusing on internal innovation versus the insights to be gained from customer feedback.

Let’s take a look.

The Benefits of Sheltered Innovation

Multiple studies have shown that individuals have a tendency to produce the most novel ideas when working alone (as opposed to crowdsourcing ideas from an external group).

But can this focus on the internal creativity of teams really have a place in the business world? Should customers be ignored?

According to Mario D’Amico, senior VP of marketing at Cirque du Soleil, the answer is, well, maybe.

In a 2012 theoretical case study published in the Harvard Business Review, D’Amico was asked what he would do about implementing customer surveys and feedback if he were in charge of a world-class dance troupe of traveling performers.

The scenario posed to D’Amico was this: A new marketing executive to the dance troupe wants to implement customer surveys in order to find out what customers want in upcoming shows. She rationalizes that knowing what customers want to see will help the company expand in the coming years.

In this case study, the theoretical company founder made a point that most CEOs in innovative industries tend to argue:

Why do we want to ask what our audience thinks? We don’t care what they think.

How can people tell you what they want if they haven’t seen it before? If we ask them what they want, we’ll end up doing Swan Lake every year!”

Does customer feedback take a backseat when innovation is the primary objective? Can customers know what they want in industries where the most successful companies are successful because they push boundaries and do the unexpected?

D’Amico, as a marketing director for a company that thrives on creativity and pushing the envelope (read more about Cirque du Soleil), has a surprisingly balanced take on the issue.

First, he empathizes with the creatives as well as the founder of the company, who claim that the company’s core mission (and the reason for their success) is founded on doing what no customer expects them to do:

Any innovative company struggles with how much to listen to customers. Most realize that you cannot trust them to tell you what your next new product will be.”

D’Amico argues that not only are creative people not fond of excessive parameters and feedback (and research has shown that external restrictions often kill creativity), but he also makes the point that in fields where companies thrive on innovation, placing too much emphasis on what customers want destroys a company’s ability to be different.

Apple’s competitive edge, he and others argue, is that they have been able to avoid the “sameness trap.” When you rely on consumer input, it is inevitable that they will tell you to do what other popular companies are doing.

How can you get ahead of the curve if your customer feedback mostly consists of today’s popular ideas?

To answer this question, we must first look at whether customer feedback is a valuable resource at all.

Do Customers Really Know What They Want?

If I had asked people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses.

–Henry Ford

A few weeks ago, when I wrote about how to implement smarter customer feedback systems, we touched on some of the data that shows customers face certain problems when they are asked to predict what they will want or use.

Problem #1: As revealed in this research by management consultant Mark Healy, customers can be terrible at predicting their future intentions when asked via a survey or a similar form of feedback. This means that even though they may be responding truthfully, their future actions won’t always match their responses.

Problem #2: No matter what businesses do to strengthen their survey methodology, sometimes customers are just going to lie in their responses.

In light of the case for innovation at the individual level, the problems with predicting customers’ intentions, and the potential lack of honesty in customer feedback … is there any point to listening to customers?

You’re likely unsurprised to hear that my opinion is yes, but it’s notable that D’Amico agrees as well.

"If the directors are smart, they’ll approve the idea of surveying customers. We use data to brief the members of our creative team, to help them understand who’s applauding when the curtain goes down.

We don’t tell them to use a red dress or a blue dress or what to do in a certain scene, but we do educate them. Then we get out of their way so that they can create.”

This statement has some significant implications, given that its source is a marketing director from a company that depends upon its creativity and pushing the envelope.

The takeaway: Customers can offer valuable insights for business. It’s worth considering that the business that is at fault when the feedback is generic and carries limited utility.

D’Amico and many others have made some subtle jabs at those who seem to be drinking the Jobs’ Kool-Aid, structuring business practices around quotes and Apple policies that may not be the best fit for their company.

What worked for Steve Jobs may not work for your company.

You Are Not Steve Jobs

So, was Jobs right or not?

Many respected entrepreneurs would say that yes, he was right ... but only for the extremely unconventional and circumstantial situation that his company was in.

When the products that your company produces are so pivotal as to be creating or redefining their product categories, and your insights are backed up with an enormously expensive creative process populated by world-class designers, then yes, you’re making the right choice by following Jobs’ lead and ignoring the customer feedback pipeline.

If customers were asked to improve the music listening experience back in a day where CD players ruled, they likely couldn’t have envisioned the iPod. But then again, you probably aren’t producing the next iPod.

But the Jobs method cannot apply across the board to all companies, which becomes pretty apparent when analyzing the results of Apple practices being employed at less similar companies.

Take for instance Ron Johnson, former VP of retail operations at Apple and the current CEO at J.C. Penny. After Johnson came on board and reformed operations at J.C. Penny, company sales dropped by double-digit percentages and stock plummeted over 40 percent.

One of the most ambitious parts of Johnson’s overhaul, the discontinuing of discounts, was questioned by colleagues who wanted to consult with customers (and gather feedback) about the new changes before implementing them.

When asked why he bristled at his peers’ suggestion, Johnson responded,

We didn't test at Apple.

Johnson’s singular rationale did not sit well with employees or others with a vested interest in the company.

Many people close to the company said Mr. Johnson ignored conventional industry wisdom and moved too abruptly to impose practices inspired by his time at Apple.

J.C. Penny is obviously a far different beast than Apple when it comes innovation. However, this situation doesn’t have to be an either/or. We’ve seen how the executive at Cirque du Soleil, another highly creative industry, has stated that understanding your customers’ wants is a pivotal part of growing your business—but doesn’t have to restrict your innovation.

If Jobs’ situation at Apple was indeed a one-in-a-million example, how can other highly innovative companies implement smarter ways to find out what their customers want without sacrificing their ability to innovate? How can they fight the “sameness trap” while getting a better handle on what customers expect?

The answers to these questions are surprisingly simple:

Find out what customers want without directly asking them.

In continuing with the example of a genre-defining dance troupe, it’s obvious that asking customers exactly what they want could result in generic answers and end up stifling creativity.

So, don’t ask that! Far more important avenues of questioning are:

What sort of things move customers emotionally

Which shows they had trouble understanding, and

What elements of shows had the strongest lasting impact.

Throw in some demographic questions to analyze who Cirque’s customers are, and you’re well on your way to a peek at customer expectations and insights—all without resorting to telling your creatives to “go with the red dress instead of the blue one.”

If you find out that shows over four hours tend to lose a huge majority of your audience and lessen the impact, you can implement this feedback into your creative process without doing “Swan Lake” every week!

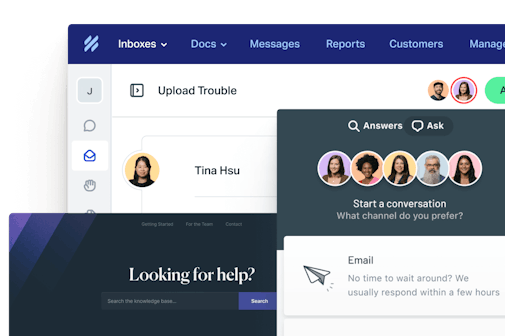

We discussed in a previous post how to implement specific techniques like this, including the “What Are You Struggling With” question, a method that small businesses can use to ask their customers (via email) what problems are bugging them the most.

This is just one method that can be used to find out what keeps people up at night without specifically asking them for feature requests, what content they’d like to see, or what move the company should make next.

With these types of goals in mind, companies can avoid the pitfall of trying to emulate Jobs in ways their business simply isn’t equipped to carry out, while also gathering valuable data about their customers that doesn’t jeopardize their creative process.

My take on the topic: Jobs’ advice has limited application (e.g., not every business should try this at home), but there is a lot of insight to be gained from his words, particularly in regards to not drowning out your own innovative ideas with customer feedback gathered from poorly framed questions.