In February I took a month off from work — completely off grid. I asked my teammates to remove my access to Slack and I stopped checking my email. I was totally absent from work for the month.

It’s been eight years since I co-founded Help Scout, and prior to February, I could count the number of days I spent “off grid” on one hand. Sure, I take vacations. But even on vacation I spend one or two hours catching up with work every morning. This time it was different.

The case for taking a sabbatical

Why now? Why take a month off at all? In my case, there were a bunch of signals telling me that time off would be positive for me personally, but that it’d be even better for the company. I’ve been in the weeds for eight years. It’d be healthy to take myself out of the mix and see what breaks, see what we learn, and watch my teammates take on more ownership.

Absence is a great measure of leadership effectiveness. When a great leader is absent, the team steps in to fill the gaps without any real disruption. Maybe that’s why I was nervous to take time off for eight years — I was afraid to face all of the ways in which I’ve failed as a leader and failed to set my teammates up for success. But in hindsight, it’s exactly what I needed to understand my leadership strengths and weaknesses.

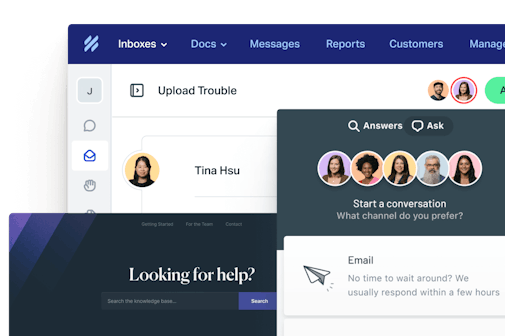

I’m so bullish about sabbaticals and their impact that we’ve formalized the program at Help Scout so that everyone can participate. Once you’ve been with the company for five years, you can take a month off. In addition, we’ll give you a $2,500 bonus to make sure you can do something fun while you are away. For every five years at the company, you get a month off and a bonus. As the company grows, I hope to move the timeframe down to three years, which feels about right to me.

Personal benefits

I love the work, but I was tired. The honest truth is that I needed a reboot. The time off gave me an opportunity to do just that, and it was everything I’d hoped for. I re-connected with my wife. I took a bunch of long walks with my dog, Elvis. I went to visit my family. And I went snowboarding for two weeks. By all measures, the reboot was successful and I felt like I had all-new software. I was re-energized, armed with new perspectives on life and work.

It’s been several weeks since I returned to work, but not a day goes by without reflecting on my sabbatical in some way. I can see the big picture more clearly. I’m more patient. It’s easier for me to not be involved in a project. I can take a half day to do some strategic thinking and planning without getting distracted. Most importantly, I can turn the laptop off or put the phone down and be more present at home — with full confidence my teammates are taking great care of the business. What a great feeling.

Impact on the company

The simple truth that’s clear to me now is that I was gripping the wheel too tightly. Loosening my grip means learning when to facilitate instead of own, advise instead of decide, and serve instead of lead.

In eight years I’ve updated my job description three times. I had a feeling that it was time to update the job description for a fourth time, and a sabbatical gave me just the right perspective going into it.

Role #1 (2011-2015): Talk to customers, build the product, repeat.

Role #2 (2015-2017): Build a team; cultivate core values and a culture people want to be part of.

Role #3 (2017-2019): Craft a long-term vision through which Help Scout can become a great business.

I don’t have a label for Role #4 yet. It’s a work in progress. But I’ve discovered a few critical skills that I’ll have to develop in the role:

1. Being grease instead of glue

When I returned to work, my colleague Chris said something that’s still ringing in my ears. He said it was “eye-opening how several processes historically depended on you being glue.”

Busted. When I was offline, I couldn’t hide all of the day-to-day decisions I had been making. I still wrote email copy. I still approved laptop purchases. I still pushed pixels around with designers. That’s why I was working a couple hours per day on previous vacations — because I made myself glue in many areas of the business, and I didn’t want anyone to notice.

Since I was making a bunch of tactical decisions every day, it meant my teammates were conditioned to defer to me instead of make decisions themselves.

The first note I wrote down when I got back from the sabbatical was, “We take too long to make decisions.” My teammates seemed indecisive; they were spending too much time gathering data and consensus. I pointed fingers for a couple days before realizing it was 100% my fault.

By being “glue,” I was minimizing the impact my teammates could have in the business. What I should have been instead was “grease.”

The best thing about being a CEO is that you can add grease to any process, project, or initiative. You can make things that are stuck get unstuck, or you can allocate resources in such a way that things move faster. Grease facilitates movement when needed, but it typically isn’t necessary for things to keep moving forward. Things fall apart without glue … but being grease is what good leaders learn to do.

2. Principles are greater than decisions

I’ve learned firsthand that making all of the decisions won’t scale, and it can become toxic for your company.

What will scale is documenting principles people can use to inform decisions that collectively align with the company’s values, tone of voice, and commitment to customers.

The tension that develops as a company grows is that a diverse group of people and perspectives are supposed to represent a single, consistent voice to the world and to customers. Most companies solve this the easy way — by layering in process, procedure, and hierarchy. A byproduct is mistrust and an inability for people to do their best work due to rigid structure.

A more thoughtful — but also more difficult — way of approaching the growth of your company is by guiding decisions with principles instead of structure. Good organizational principles make it so that your diverse team is guided towards a consistent way of thinking without being stripped of their decision-making authority. It’s more difficult because in a 100-person company, you have 100 decision-makers. However, I think the benefits far outweigh the downsides. It allows high performers to shine.

A must-read on this topic is a book by Ray Dalio, appropriately titled Principles. Instead of calling all the shots in his company, Dalio has refined a set of principles over several decades, which exist to empower others. He defines a principle as follows:

“Principles are fundamental truths that serve as the foundations for behavior that gets you what you want out of life. They can be applied again and again in similar situations to help you achieve your goals.”

Principles shouldn’t be heavy-handed or overly prescriptive. A few that come to mind for me at Help Scout include:

Nothing is more important than maintaining our integrity as a brand.

Make sure the work we’re doing reinforces and raises our standards for excellence.

Customer service professionals are our people. Create products and resources that make them feel more powerful.

As a minimalist, I’m not a big fan of creating organizational overhead. Principles feel like unnecessary overhead until they aren’t. When they make people feel like owners, like they have a mandate to impact the business, principles should be a welcome addition. It’s a much better approach to the alternatives: top-down decision making or consensus-based bureaucracy.

3. Closing the loop

Another thing you have to be intentional about in a company with so many owners and decision-makers is closing the loop — communicating key decisions with the rest of the company. Making sure everyone has access to the same information is already a cornerstone of remote work, but larger teams require more and more structure to keep their teammates in the know.

I recently did some reading on Scott Dorsey, the visionary founder and CEO of ExactTarget. Scott was CEO from day one through their successful acquisition by Salesforce for $2.4 billion about 12 years later. One of the most powerful tactics that he implemented in his time there is fondly known as the “Friday Note.” Here's how Scott describes it:

“I started officially sending out my ‘Friday Note’ in 2009 and never missed a weekly email for over five and a half years. It was a simple and very impactful way to highlight accomplishments for the week and keep the lines of communication open with our 2,000+ employees. It showcased the transparency in the company and helped us keep our unique ‘Orange’ culture as we scaled the company — one of the defining factors to our overall success at ExactTarget.”

Our CMO, Justine Jordan, worked for Scott at ExactTarget early in her career and raves about how this seemingly simple tactic had a profound impact on people in the company. It was so profound in fact, that when Scott left the company, the employees compiled all of his Friday notes into a book and gave everyone a copy.

I’ve started experimenting with writing Friday Notes at Help Scout. I don’t know if I’ll keep it up for over five years, but I’m convinced that a high volume of passive communication in a growing company connects people. It connects them to each other, to the mission, and to a vision they feel responsible for.

I’m eager to experiment with new ways for our team to communicate with each other, in hopes that improved communication will better inform the decisions people are making daily.

Just do it

My sabbatical learnings will be different from yours, but I’m betting that, in any case, the experience will be transformational both personally and professionally. Once you’ve been working on something for at least three years, it’s important to take a step back and see what the universe has to teach you. No excuses … just give it a go. I’d love to hear your story when it’s over.