The further you get in your career, the harder it is to pinpoint — and then do something about — your personal and professional shortcomings.

Why is that? You’d think leaders especially would be skilled at identifying and removing obstacles. But as career coach Marshall Goldsmith explains in What Got You Here Won’t Get You There, “We get positive reinforcement from our past successes, and, in a mental leap that’s easy to justify, we think that our past success is predictive of great things in our future.”

In other words, we think we got to where we are because of the way we are and what we’ve done — not in spite of it. In many cases, that’s wrongheaded. Our shortcomings do hold us back, but it doesn’t have to be that way.

The shortcomings you can’t see

Unless you’ve reached enlightenment, chances are you have at least a few unidentified, unaddressed shortcomings (often referred to as “blind spots,” though I prefer the term “derailers” because it’s a less ableist way to connote shortcomings large enough to cause your career to slide off track).

The further we advance in our careers, the less these derailers have to do with “hard skills” and the more likely they’re personal and behavioral in nature. Perhaps you’re unaware of how consistently negative you are in meetings. Maybe you make excuses rather than accept responsibility. Do you value being right over being effective? Claim credit you don’t deserve? Fail to listen? Behave as if the rules don’t apply to you?

If you think, “Sure, but that’s just who I am” — that’s a derailer too.

Over time, Goldsmith says, it’s easy “to make a virtue of our flaws — simply because the flaws constitute what we think of as ‘me.’ This misguided loyalty to our true natures — this excessive need to be me — is one of the toughest obstacles to making positive long-term change in our behavior.”

What tricky little justification machines our brains are! We’re so adept at downplaying the significance of how others perceive us, not to mention how skilled we are at identifying others’ shortcomings over our own. The good news: you can solicit honest feedback and act on it in ways that help you overcome these potential career derailers.

Why it’s hard to solicit feedback

1. We don’t want to know

Fact is, our derailers are holding us back whether we acknowledge them or not. Claire Lew, CEO of Know Your Company, says some of the most common refrains she hears from CEOs are “I don’t know if I want to know everything” or “I feel like I’m opening Pandora’s Box.” She tells them yes, they might hear feedback they don’t necessarily want to — but the reality is that “those things exist whether or not you choose to address them or learn more about them.”

2. We don’t want to look incompetent

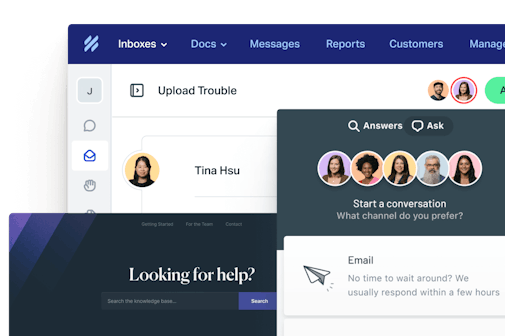

Especially among leaders, there’s a concern that asking for feedback makes it look like you don’t know what you’re doing. “If you’re the person people look to for answers, but you don’t have the answers, then your team may not think of you as a strong leader,” says Help Scout CEO Nick Francis. “As a leader you’re always making big bets, or making assumptions and going out on a limb with regard to a product or market or whatever. Typically that doesn’t lend itself to asking for advice.”

3. No one wants to be the messenger

I once begged my best friend to tell me what my weaknesses were, the ones I couldn’t see for myself. She didn’t want to say. “How can I change for the better if I don’t know what I’m doing wrong?” I pressed. “Some conversations are better off not taking place,” she told me.

People don’t want to be the bearer of negative feedback because they fear negative consequences.

This is especially true when the feedback-seeker holds more power; who wants to inform her supervisor that he has a nasty temper? We anticipate that the recipient of our feedback will assume we are confused or wrong, and that they will discredit our message. We expect them to take it personally and get defensive. It doesn’t take a sophisticated cost-benefit analysis to decide it’s easier to put up with the behavior than to speak up.

How to solicit critical feedback

So you can’t simply go to your team and demand to know what your weaknesses are. They probably won’t tell you, and (let’s be real) you’d probably get defensive if they did. Instead, follow these steps to solicit honest, actionable feedback about what you could be doing better.

1. Ask questions

Lew advises a “genuinely curious” mindset about your own areas for potential improvement. “Answers only come when you ask questions,” she says, and the more specific those questions, the better. Asking a teammate “What weaknesses am I oblivious to?” won’t get you nearly as far as asking “What’s one thing I could be doing differently on a day-to-day basis that would improve communication?”

2. Frame feedback as advice

“It’s always scary to call it ‘feedback,’” Lew says. Instead, she recommends asking specific questions like “Do you have any advice about how we should handle recruitment in the company?” or “Do you have advice about how to prepare for our client meetings?” This technique works because people love giving advice. “Everyone likes to think of themselves as an expert and to share their perspective,” says Lew.

3. Just say ‘thank you’

When you’re receiving feedback, the temptation in the moment will be to react — to defend yourself, explain, judge, apologize, whatever. Resist this urge. Just listen without interrupting, Goldsmith advises. Don’t finish the other person’s sentences or let your attention wander elsewhere. The only thing you’re allowed to say is “thank you.”

4. Write it down

One technique for listening without judgement is to write down the advice you’re receiving. “Even if you’re not a note-taker per se,” Lew says, it shows the other person “you’re taking into account what they’re saying, that you’re not just asking for the sake of asking.”

What to do with that feedback once you get it

This is the hard part: Once you’ve learned what your derailers are, you’ve got to act in some way that honors the people who were brave and honest with you. (Otherwise, good luck ever getting honest feedback again.) Commit to action. Share your plans for change with those around you so they can help hold you accountable.

When Cathy Atkins, founding partner at Metis Communications, decided to move away from the firm’s Boston headquarters, she didn’t expect all the pushback she got from her team, who thought she’d lose touch and the work would suffer. “It really took me aback,” Atkins says. “I always valued my working and personal relationships and didn’t think they were a result of sitting physically next to people.” After the initial sting, however, Atkins educated herself on remote best practices — reading books, speaking with folks at other remote companies, and researching technology. It worked. “I value the face time so much,” she says, “but I also am proud that our team has the option to move and still work with us.”

By following up, you show your team you not only respect their opinions, but value them highly enough to make real changes. “The people who really are able to make the greatest contributions to their company and the ones who have the biggest impact on their coworkers and customers,” Lew says, “are the ones who get feedback and then react almost immediately.”

Without follow-through, none of this matters

If you want to make great contributions to your company and have a positive impact on your coworkers and customers, you can’t ignore your derailers. Find out what they are, and then commit to a process for change.

Despite a mentor’s advice to step away from the keyboard and wait at least 12 hours before giving critical feedback, for example, Nick admits he still struggles with getting emotional over little things in the moment. “It could be something is misplaced by five pixels and I get really bent out of shape,” he says. While he no longer indulges in long email arguments or counterpoint essays, he says he can still get riled up in chat and say things he later goes back to apologize for. The 12-hour rule has been “incredibly valuable,” Nick says, but “I still have to coach myself on it constantly.”

“People don’t get better without follow-up,” Goldsmith writes. “Following up consistently, each month or so, shows that you are taking the process seriously, that you are not ignoring your coworkers’ input.” By regularly checking in with yourself and your team about your progress, you make the shift from knowing what you need to change, to actually changing it.