When a guest author hands me their first sample draft, it’s often missing a conclusion — sometimes accompanied by a note of apology that they thought about it, but they don’t know how to wrap the darn thing up, and could I offer any suggestions?

I don’t blame them — conclusions are often the most challenging part of any piece, and there’s a lot of conflicting advice about how to handle them. What follows is the most common advice I share with guest authors who are struggling with writing a conclusion that resonates.

Why writing conclusions is difficult

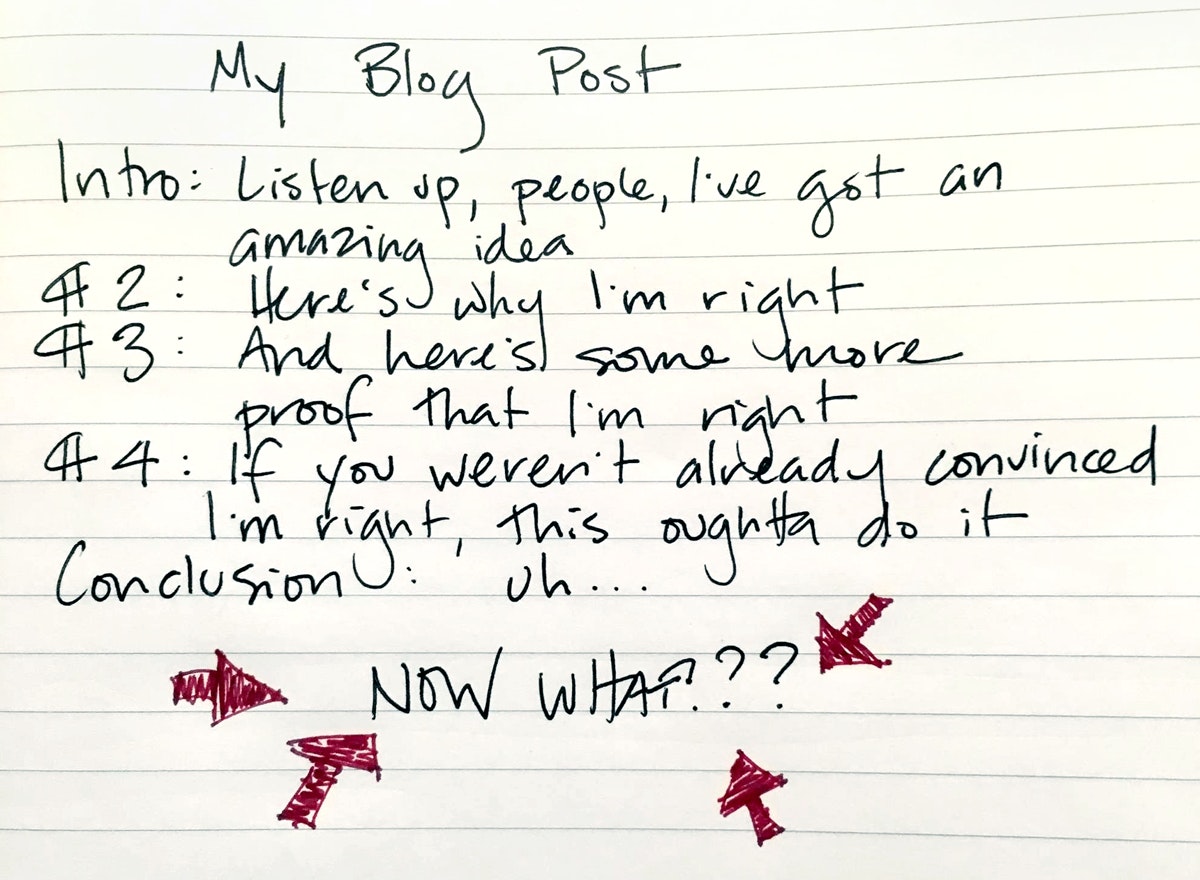

Remember your English teacher offering some form of the following advice about how to structure an essay or thesis statement?

Tell ’em what you’re gonna tell ’em, tell ’em, and then tell ’em what you told ’em.

It’s not terrible advice for a beginning writer — while the five paragraph paper has its faults, it’s a useful mechanism for learning to think critically and structure straightforward arguments. The advice breaks down, however, as soon as anyone wishes to communicate a moderately complex idea to anyone other than the person reading your paper.

Yet further conventional wisdom about how to approach conclusions can be vague and conflicting: Restate your main points, but don’t repeat yourself, but do make sure you summarize the entire piece, but definitely don’t introduce any new ideas. Make sure you signal this is the end, but don’t use the word “conclusion,” but do leave your reader with an interesting final impression …

No wonder so many folks find conclusions impossible.

A great conclusion answers the ‘so what?’ question

Regardless of length and format, it’s common to get to “the end of the middle” of whatever you’re writing and not know where to go from there.

You already said what you meant and offered a pile of evidence to prove your point! What else is there to say?

A great way of concluding your piece is to answer the “so what?” question. It sets your idea in a broader context, which gives your writing a better chance of resonating with a larger audience. Take a step back from what you’ve been saying and ask: Why is this important? Why should anyone care?

Take Nick’s post on “Parting Ways With a Remote Employee.” It’s a list of tips about how to let go of an employee when you can’t be in the same room. The topic is a) ugly and b) probably irrelevant to most readers. But Nick does a nice job answering the “so what?” question in his conclusion:

This conclusion tells the reader what they’re supposed to take away from the post. Why is this important? Because there’s another human being involved in this situation, and they’re having a much worse day than the person doing the firing. Why should anyone care? Because if you take the advice Nick gives in this post, that person will have a better (at least, less horrible) experience, and ideally go on to succeed somewhere where they’ll be a better fit, and you can be a part of that.

Nick’s conclusion works because it takes the advice he gives throughout the post and applies it on a wider scale, at a more human level. The lesson applies to anyone who’s ever had to let someone go, not only remote teams.

Make it human

Getting personal is another good trick for writing conclusions that make an impact. How can you apply what you’ve just said not only to your work, but to your existence as a human on this planet?

That’s what I was going for in the conclusion to “Why You Should Set Big Goals (Even If You Might Not Hit Them)” — the post is about the benefits of thinking big, and why Help Scout tends to aim for goals higher than what we think we’re capable of accomplishing. It’s something I’ve started doing on a personal level, too, because left to my own devices, I won’t aim high enough — so I used the conclusion as a space to own up to that, in case any readers identify with that feeling and might get value out of asking themselves the same questions.

Ask a question or issue a personal challenge

Your conclusion is your last chance to make a powerful impression on the reader — you want what you’re saying to stick with them, to resonate and offer a sense of completeness.

What I want most of all is resonance, something that will linger for a little while in Constant Reader’s mind (and heart) after he or she has closed the book and put it up on the shelf.

Stephen King

Addressing your reader with a direct question or personal challenge invites them to sit with your idea and apply what you’ve said to their own situation.

In the previous example, in addition to asking the reader whether they’ve set any big goals, I challenge them to to examine whether they’re selling themselves short by setting small, easily achieved goals. Dave Martin issues a similar challenge in his conclusion to “How to Work a 40-Hour Week”:

Dave’s post is about how to maximize your working hours — tracking your time, creating an action plan and coming full circle. But his conclusion — that if your work-life balance is out of whack, you need to take some time to think about why that is, and be prepared to make some big changes — takes his advice several steps further. He answers the “so what?” question, and applies the post’s message on a greater, human level. It resonates.