If you were designing a race car, how would you do it? Make it go faster, you would tell yourself. Just beat everyone as fast as possible.

Building a faster car is a typical first approach, but when developing a car for the famous 24-hour Le Mans race in 2006, the chief engineer of Audi asked a brilliant question instead: “How could we win Le Mans if our car could go no faster than anyone else’s?” If it couldn’t go faster, how did they expect to win?

This propelling question tied a bold ambition with a significant constraint to push the Audi team to develop their first-ever diesel technology car—the R10 TDI. The answer was fuel efficiency. By making fewer pit stops, the Audi car didn’t go faster, it merely lasted longer. The R10 TDI placed first in Le Mans for the next three years.

In their must-read book, A Beautiful Constraint, Adam Morgan and Mark Barden shared this brilliant example of how Audi leveraged constraints to provide an entirely unique approach to the problem.

If they can do it, then so can you. Let’s look at how to make constraints work to our benefit.

How we view constraints

In A Beautiful Constraint, Morgan and Barden share the three mindsets that we fall into when dealing with constraints:

Victim: Someone who lowers his or her ambition when faced with a constraint.

Neutralizer: Someone who refuses to lower the ambition, but finds a different way to deliver the ambition instead.

Transformer: Someone who finds a way to use a constraint as an opportunity, possibly even increasing his or her ambition along the way.

To shift from one mindset to the next requires self-awareness: what exactly is the narrative that you’re telling yourself about this obstacle ahead of you? Only after you identify the dominant story can you change your mindset.

Here’s an example: A man runs a local bakery and the rent just went up 20%.

“Looks like I just have to pay more,” the baker with a victim mindset would say. “I can’t move right now. The time isn’t right.”

A neutralizer is resilient in his or her ambition, but also devises new strategies to work around the constraint. “I must have this store, but maybe I can also start a website in order to expand the business and offset the rent increase.”

A transformer leverages this loss as an opportunity to rethink the business. “What if I don’t need a physical store? What if I only sell online or what if I send baked goods as a subscription service?”

Each story the baker tells himself shapes his attitude, and his behavior follows. It’s a self-fulfilling prophecy: what he believes about his options determines what he does and, ultimately, the outcome he creates.

Here are some ways to change the way you approach constraints.

Ask propelling questions

When faced with a particular limitation or constraint, it’s helpful to begin with asking propelling questions to remove the frames you’ve placed around the problem. Barden and Morgan expound:

“Propelling questions bind a bold ambition to a significant constraint. The solution has to make use of the constraint, denying us what would make the answer easier, ensuring that we address real challenges and not indulge in blue-sky fantasies. A propelling question is most powerful when it has specificity, legitimacy, and authority.”

Often, the framework of propelling questions can be best understood with can/if solution-based thinking.

The man who runs the bakery could ask himself the following:

How do I make up for the 20% increase in rent? Can I be unaffected by the increased rent if I diversify the menu with items that customers want?

Can I improve the customer experience and get more people to come in if I set up chairs and tables outside?

Can I remove the items that haven’t been selling as well and capitalize on pushing my best sellers?

None of these are guarantees, but asking questions can get you unstuck and allow you to creatively explore the possibilities that exist.

Turn personal constraints into learning opportunities

Mark McMorris is an iconic Canadian snowboarder who won back-to-back gold medals in the Winter X Games and brought home a bronze medal from the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi. It was Canada’s first medal from the games.

You would think someone with such passion and talent was born on top of the mountain, strapped into a snowboard the day he was born. Quite the opposite—McMorris was born and raised in rural farmland in the province of Saskatchewan.

He and his brother, Craig, “scratched tooth-and-nail” to be on a snowboard. But the restricted access was their greatest constraint, and because of their passion for the sport, they found other ways to hone their skills.

Wakeboarding, skateboarding, surfing, and jumping on a trampoline—McMorris developed his skills in these other sports because they had a fundamental connection to his love of snowboarding.

What could have been his greatest constraint was leveraged to become one of his greatest advantages, and his ability to view his supplementary hobbies in a positive light was simply good perception.

Self-impose constraints to create growth

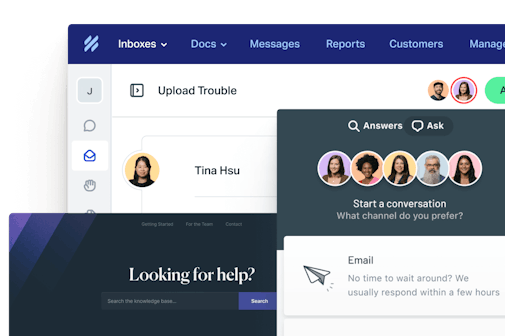

Help Scout co-founder Nick Francis wrote about the importance of constraints in doing good work and in the hiring process. He notes that in order to keep an overachieving culture, he’d rather have 10 overachievers doing the work (and getting paid the amount) of 30 people, because it gives each employee more ownership and motivation to meet the customers’ needs.

“By way of embracing this constraint, every person has to perform at a high level. . . . In the same way I believe less funding has extraordinary benefits for early stage companies, fewer people (each with a lot of ownership) brings about a culture of overachievers. They get more done in less time and foster a “we’re in this together” attitude.”

He also writes about the benefits of being underfunded. When money is a constraint, businesses must spend wisely, work diligently, and grow thoughtfully. “Screw finding an office space with a sweet kitchen. You've got to focus on acquiring customers and reducing your monthly cash burn. In most every case, this puts your focus squarely on the right things.”

With the right lens, opportunities abound

Constraints will always be part of the work. If they aren’t obvious now, they will surface sometime in the future, either intentionally or surprisingly.

Self-awareness in this respect is crucial to understanding the mindset that you’re embracing—victim, neutralizer, or transformer?

Once you know the dominant narrative, you can ask yourself propelling questions to break apart from the path to objectively look at the obstacle ahead of you.

Doing this sets you up for success because you’re seeking to adapt rather than refusing to change.

It opens up your mind and makes you squint to pay closer attention to the details—the subtle insights that fly under the radar but have enormous potential for innovation.

Before you know it, you’ll realize that you have all it takes to flip constraints into advantages. All you have to do is put on a new pair of glasses and, in turn, tell yourself a different story.

As the emperor and philosopher Marcus Aurelius said in his work Meditations, “If you are distressed by anything external, the pain is not due to the thing itself, but to your estimate of it; and this you have the power to revoke at any moment.”