Reinvention always meets resistance. From pivots to process changes, it’s tough to have a perfectly smooth transition.

In a New York Times article titled “Why You Hate Work,” Tony Schwartz and Christine Porath explore why most people hate their jobs. Through surveys partnered with Harvard Business Review and reports by Gallup, they discovered what employees truly desire in the workplace.

Schwartz and Porath conducted a pilot program with 150 accountants from a single firm during tax season—a daunting time where stress and burnout spread like wildfire. They persuaded the firm to try a new strategy: utilize the practice of intermittent rest, including 90-minute periods of focused work followed by a short break, give full one-hour breaks in the afternoon, and allow employees to leave when the work was finished.

The results? These employees got more work done in less time, left work earlier, reported lowered stress, and their turnover rate was reduced.

Sounds like a win-win, but there was one paragraph in the article that left me utterly confused:

Senior leaders were aware of the results, but the firm didn’t ultimately change any of its practices. “We just don’t know any other way to measure them, except by their hours,” one leader told us. Recently, we got a call from the same firm. “Could you come back?” one of the partners asked. “Our people are still getting burned out during tax season.”

Why, oh why, is complacency so tempting?

What this story reflects is not limited to accounting or even the firm in question, but rather human nature and the difficulty of changing one’s mind. Businesses (and leaders) that thrive and not merely survive are able to honor and understand the need to adapt when feedback exposes their flaws.

Human nature is stubborn, however.

The fine (and scary) art of self-justification

In Mistakes Were Made (But Not By Me), Carol Tavris and Elliot Aronson share a fascinating study on confirmation bias, why it's so hard to change our minds once they’re made, and what we do when faced with an opposing point of view.

Indeed, even reading information that goes against your point of view can make you all the more convinced you are right. In one experiment, researchers selected people who either favored or opposed capital punishment and asked them to read two scholarly, well-documented articles on the emotionally charged issue of whether the death penalty deters violent crimes. One article concluded that it did; the other that it didn’t. If the readers were processing information rationally, they would at least realize that the issue is more complex than they had previously believed and would therefore move a bit closer to each other in their beliefs about capital punishment as a deterrence.

But dissonance theory predicts that the readers would find a way to distort the two articles. . . .This is precisely what happened. Not only did each side discredit the other’s arguments; each side became even more committed to its own.

This tension is called cognitive dissonance: the feeling we get when two opposing beliefs collide into one another, e.g., “I’ve been an experienced business leader for over 20 years” and the realization that “My business is failing.”

We reduce cognitive dissonance with self-justification; we rationalize and fabricate a story that ultimately makes us feel better about the decisions we’re making and why. Without self-justification, we would be lost in endless outcomes and lose sleep over what we did or didn’t do.

Tavris and Aronson share the neuroscience behind the difficulty of changing our minds and why this is part of our nature:

Neuroscientists have recently shown that these biases in thinking are built into the very way the brain processes information — all brains, regardless of their owners’ political affiliation.

For example, in a study of people who were being monitored by magnetic resonance imagining (MRI) while they were trying to process dissonant or consonant information about George Bush or John Kerry, Drew Westen and his colleagues found that the reasoning areas of the brain virtually shut down when participants were confronted with dissonant information, and the emotion circuits of the brain lit up happily when consonance was restored.

These mechanisms provide a neurological basis for the observation that once our minds are made up, it is hard to change them.

There’s a reason why organizations hire consultants, why authors hire editors, and why athletes hire trainers: someone who isn’t as emotionally attached can be objective in their analysis and help create clarity in understanding what’s broken and how to fix it.

Still, even with resounding evidence that another process is more fruitful, the story of the accounting firm shows how difficult it is to make hard left turns.

It doesn’t mean it’s impossible—the Red Cross did this effectively—but it’s an obstacle that your business will face; in fact, it may be a defining moment.

If minds change, they change slowly

“The dogmas of the quiet past are inadequate to the stormy present,” said Abraham Lincoln in December of 1862. “The occasion is piled high with difficulty. As our case is new, so we must think anew and act anew. We must disenthrall ourselves and then we shall save our country.”

Yes—disenthrall!

To fix the things that are broken, we must gain a level of objectivity through clarity and expect the hurdles of changing one’s mind.

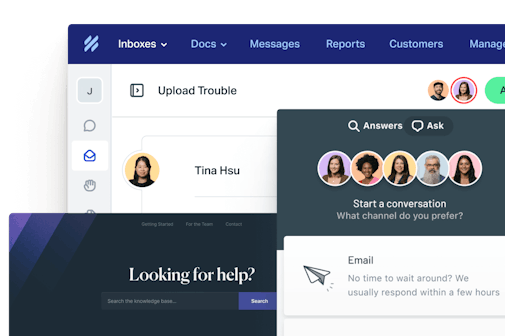

Recently at Help Scout, we had Becca, one of our Customer Champions, come in and help us improve the content marketing process. From where I stood, everything was fine; when I was asked for suggestions, I really couldn’t think of any. To me, the engine was humming beautifully. When Becca introduced Asana as our new system, of course I felt resistance—I was used to how things were done!

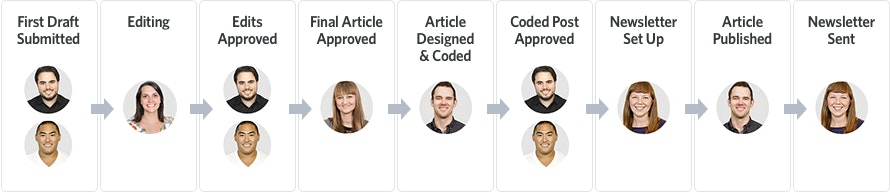

She sent this via email to showcase what the new system would look like:

The old system? I wrote something, uploaded it to Dropbox, pinged people, waited around, and grabbed whatever fell into my inbox. At that time, this was a good process to me.

Becca provided the big picture on how this system would improve our content marketing process, as well as why it would be suitable for the long haul. By walking us through Asana and having short meetings on suggestions or concerns, within weeks I adapted to the new process as if I had been using it for years.

It’s only in hindsight that I was able to see all the kinks in the old process. I was so comfortable and emotionally attached that it blurred my ability to see something for what it was, and even more alarming, to conjure up innovative ideas for improvement.

With the new system, there’s accountability and fluidity. There’s a definitive process versus one that fluctuates. Not only is this good for us now, it’s good for the future.

Working toward change

Every business, no matter how great things may seem, needs to exercise the following three behaviors in order to reach a level of objectivity that allows clarity.

1. Have self-awareness: Can we look at our actions objectively and critically? Can we understand our behaviors and the outcomes they produce? Can we break out of the cycle of self-justification, relentlessly rationalizing that things are okay when they really aren’t?

2. Ask/hire for help: Do we need a fresh pair of eyes to help us see better? What are others seeing that we’re missing? How would someone else do this? How long have we been doing things the wrong way, and why?

3. Devise a strategy: We know what’s broken, so what’s the strategy that utilizes the feedback? What tools do we use? How does this unfold? When do we start? How does this benefit the organization, the team, and the people we serve in the long haul?

Author Michael Perry said it beautifully: “We accrete truth like silt. It hones us like wind over sandstone.”

Change, whether in our personal lives or the organizations we work in, will always be difficult. Exaggerating the point in order to make it, we see cognitive dissonance play out in unfortunate situations like Kodak not being willing to let go of film in favor of where digital photography was headed. But there are also success stories: Denise Morrison, CEO of Campbell’s soup, said it took time to “get a 145-year-old company to embrace change” but that getting the organization to stop resting on its laurels was a key part of the turnaround.

Self-justification may behave like quicksand, but by being aware of our attitude and behavior when meeting with an opposing perspective, we can choose to be more mindful and self-aware in our analysis and how we utilize the feedback.

Businesses, like humans, are works in progress. Suddenly realizing that what you’ve been doing is suboptimal is always uncomfortable, but that’s part of the game. Reinventing old processes is often a high-effort, high-reward activity.

It takes guts to critique what’s accepted, standard, or “how we do things,” but showing that there are indeed more effective ways to encourage a better workplace in turn helps build a better business.