If you search for advice on creative thinking, there’s plenty to be found on how to be more creative but little written on how to avoid blocking others’ creativity. Why is that?

Most of us would like to believe we’ve never stifled the creativity of our colleagues. But it’s easier to do than you think, and it always starts with the best of intentions. When you’re on a team, the environment you contribute to is even more important than your individual work, which makes avoiding these pitfalls a high priority.

The formative steps are where teams have the biggest impact on any new idea. Our colleagues get to see the mocks, rough drafts, and specs, and can have a significant influence on how they develop, usually for the better. But this nascent stage is also where groups need to be the most cautious. Here are four mistakes every team should look out for when creating an environment conducive to creative work.

1. Creating a culture of defensiveness

Expecting your first idea to be right places undue stress on the creative process. Solutions become more obvious when you fill in the gaps around them with trial-and-error. Studies even show good, novel ideas rest on the willingness to continually rethink a problem.

Unfortunately, this straightforward reality is made complicated thanks to human nature. We have to share projects internally before a “final” version can be put into production, but early thoughts are the most fragile because we’ve yet to build a strong case for why they might work. As a result, we’re prone to either not suggest an idea at all, or we prepare for critique by putting our guard up.

The latter is a killer because it results in excessive “presentation,” wherein people build cases more developed than their actual ideas. This is similar to editing before a rough draft is complete — it’s a form of self-censorship, where high standards are applied at the wrong time. Even worse, effort spent defending an idea is still a sunk cost, and you’ll end up becoming attached to the ideas you present, even if you aren’t especially confident in them.

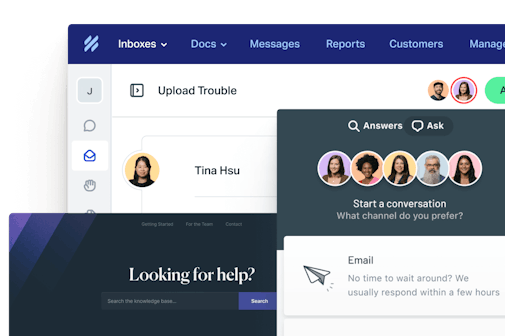

Avoiding this problem is all about the tone you set. Professor Teresa Amabile of Harvard found that phrases like, “We do things by the book in this department” can discourage people from suggesting new ideas. Walking cliché aside, you can create a similar situation with the language you choose. Our editorial team noticed this recently: We used to call all new stories “pitches,” which had people questioning how secure and fleshed out their ideas needed to be before getting feedback. We renamed that stage so it was clear these were concepts that could be worked on, not pitches that needed defending.

You’re probably not surprised to hear that our “Ideas” inbox runneth over, whereas the “Pitches” column was more famine than feast. More importantly, the “Ideas” column is filled with better, well, ideas. In the earliest stages of the creative process, lowering the barrier to entry can help raise the collective bar.

2. Forcing synthesis work to happen in groups

The research and written sermons denouncing group brainstorming are pretty convincing. I’ve noticed most of the cited problems also show why meetings aren’t ideal for synthesis work:

1. Social loafing. Knowing the group can collectively pick up individual slack causes some people to minimize their contributions or go silent on important points (“Someone else will mention it…”).

2. Production blocking. When other people are talking, the rest of the group has to wait. This can cause contributors to lose focus on their ideas or dissuade them from speaking at all.

3. Evaluation apprehension. Although many brainstorming sessions try to leave evaluation out until later, everyone knows the group is quietly reacting to their ideas as soon as they hear them.

There’s another hidden danger: compromise. Meetings are conducive to compromise because they dilute the average level of experience in a setting built around spontaneous suggestions. The result is a collective search for common ground, and common ground is most easily found on the simple issues.

So while a good meeting should be about alignment, not agreement, the implicit agenda becomes “find something we can all agree on.” Since off-the-cuff justifications are always present in live debates, it’s easy to see why the loudest voices commonly win the day.

Groups will always be better at piecing things together than they are at creating the individual pieces.

But meetings and brainstorming clearly have their place. One of the reasons that “brainwriting” — the practice of submitting ideas as a group through written text or chat — has become a popular practice is because it minimizes the problems of brainstorming while amplifying the main benefit: collecting a large pool of ideas that aren’t shot down before they’ve had time to simmer.

3. Offering feedback before asking questions

When we hand out unsolicited or ad-lib advice, we’ll often try to prevent it from being taken too seriously by saying, “Just my two cents.” But feedback, positive and negative, can be influential, even when the speaker thinks little of it.

Instead of giving immediate feedback, ask questions. Similarly, when you’ve just begun working on an idea yourself, ask for clarifying or developing questions over direct feedback or critique.

Why is that? Questions are expansive rather than limiting; they’re more likely to open people up to alternative ideas or prompt counterfactual thinking that leads them to a better answer. Critiques, even in good spirit, are always seen as a challenge to what’s there. They’re more restrictive, and they feel like a hunt for visible faults instead of an inviting focus on “What if?”

As my college professor used to say of his book writing process, “Start with boundless optimism, followed by unceasing paranoia.” The later stages are best for critique, criticism, and inversion as you look for what could go wrong. But a fresh thought usually needs a bit of encouragement, “critical thinking without criticism,” so to speak — be careful to not trample it with an immediate reaction.

4. Applying the wrong amount of process

A blank canvas imposes the burden of unlimited scope. When you can do anything, being overwhelmed by choice often makes “nothing” the most enticing option. Moreover, it’s hard to maintain quality when literally everything goes, because there are too many variables to control for.

Process is the great elixir, but as Jason Fried has pointed out, process and policy can become “codified overreactions” to simple mistakes or fear of the unknown. This leads to a bureaucratic mess, where even chance thoughts have to be run through the meat grinder of process.

Like many tradeoffs, the right balance between order and freedom is key. The best description I’ve seen of this happy medium comes from Pete Myers of Moz, who says process should make creative work repeatable, but not repetitive.

Adapted from a keynote given by Pete Myers at Mozcon

Editorial teams live with this problem. You’ve got to give writers, teammates, and guests room to have a voice in their writing, but still provide enough structure to wrangle in the person who wants to submit an interpretive dance as their next blog post.

One way we’ve personally worked on this issue is to create “article archetypes,” or repeatable approaches to publishing a good idea. You won’t have your thoughts templatized to hell, but there’s enough structure to create a relatively consistent feel on our calendar, from original pieces, to product updates, to interviews, and everything in-between.

On temporarily lowering your standards

If you take a look at the points above, you’ll notice all of them start with a positive outcome in mind: Making “improvements” in process, critique or headcount should have encouraged better ideas, but they didn’t. Why not?

It’s because every medium has a rough draft stage, and every person responsible for problem-solving needs to run into a bunch of mistakes before they can find a suitable answer. Paradoxically, you’re best suited to hit high standards when you work in an environment that lets you to start with lower ones.

When faced with writer’s block, a common piece of advice is to temporarily lower your standards. It’s based on the idea that the work isn’t always what’s in the way; sometimes it’s you.

When creativity is blocked by an especially tough problem, getting a new perspective helps. Here are “3 Approaches for Getting Unstuck.”