What can your business do about customers who are reluctant to part with their money?

First, it helps to stop seeing these customers as “cheap” or “tightwads” (although the title of the article suggests otherwise because that is what scientists call them — more on that research in a moment!), and instead recognize that “cheap” customers simply feel more “buying pain” than other types of customers.

In other words, the way to deal with cheap customers is to reframe the problem.

“Cheap customers” are simply folks whose brains are wired to feel more buying pain than other individuals — they’re harder to sway in their purchasing decisions because they feel more pain for each purchase. That’s especially crucial info for small to medium-sized businesses, where nearly one on four customers fit the “tightwad” persona.

The question, then, is this: How can businesses successfully sell to “cheap” customers without wasting everyone’s time?

3 types of paying customers: Tightwads, Unconflicted, and Spendthrifts

Neuroscientists have literally defined human spending habits as “spend ’til it hurts.”

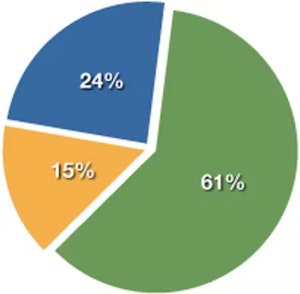

Numerous studies on “tightwads vs. spendthrifts” have demonstrated the following spread of customer types:

Tightwads (24%) — people who spend less than they would ideally like to spend

Unconflicted (61%)

Spendthrifts (15%) — people who spend more than they would ideally like to spend

Conservative spenders make up a large portion of the average customer base, so easing their pain should be a priority.

One subset of these conservative customers, sometimes called “barnacle customers,” isn’t worth trying to sell to at all — we’ll address that later on.

For now, just know that your typical “tightwad” is not a customer who isn’t able to see value in full prices. Cheap customers aren’t necessarily bottom-dollar sale chasers; they just have a harder time parting with their money.

Fortunately, there are ways you can ease their buying pain that won’t affect your other customers.

Get ‘cheap customers’ to buy, by minimizing their buying pain

Among some incredible research using neuroimaging that breaks down the neural process of purchases, as well as the research cited above from Carnegie Mellon University, we’ve found some consistent ways to appeal to thrifty customers that doesn’t affect your other customers (especially your more willing spenders).

Here’s what you can do ...

1. Reframe your product’s value

While all humans struggle with large concepts of time and money, this process is even more difficult for conservative spenders.

It’s harder for so-called “tightwads” to rationalize expenditures when the length of time and price point are at their most abstract: for instance, when deciding to pay a large price for a product or service for a full year.

For instance, paying $1,000 a year for a continually used product or service makes it tough to grasp its actual value. When selling to these customers (and all customers), it’s better to break pricing up into segments that makes value calculation easier to stomach.

For instance, at that price point, you can create an offer around $84 a month, which makes it easier to assess the value a customer might get from your offering. Additionally, you could take things further by going with, “for as little as $2.75 a day!”, giving customers an exact daily value for your product.

Being able to say: “This product solves enough problems that it’s worth a little more than two bucks a day” goes a long way in convincing customers who can’t see the value at $1,000 per year.

For one-off purchases, be sure to highlight life-expectancy of the product: an expensive camera will seem a lot more interesting if the quality makes it feasible to last 5+ years and still take fantastic pictures.

2. Bundle products to reduce recurring pain points

Neuroeconomics expert George Loewenstein has noted that all customers (but especially conservative spenders) are averse to buying multiple accessories if they can complete their purchase in one swoop.

One example he cites is how car manufacturers often bundle accessories in the form of a “plus package” in order to reduce the number of individual purchases: Few people could handle the pain of buying not only the vehicle but also leather seats, digital navigation, an upgraded sound system etc., but many people opt for a better package when it comes all together.

The reason this works is that these individual purchases force us to make a specific decision for each transaction, even if our “end goal” is just a generally upgraded vehicle.

By offering combined packages (for our digital camera example, imagine throwing in a memory card and a case), all of your potential customers can reduce their buying pain to one transaction if they so choose, and you’ll have offered another unique value perspective for hesitant tightwads.

3. Pay attention to the details

One of the more surprising findings from the aforementioned research is just how true the expression, “the devil is in the details” is for conservative spenders.

Minor changes in language — microcopy — can greatly affect customer’s reactions and receptiveness to making purchases.

A “small” change creating big sales

The CMU studies revealed that changing the description of an overnight shipping charge on a free DVD trial offer from “a $5 fee” to “a small $5 fee” increased the response rate among tightwads by 20 percent!

Let’s put those two offerings side-by-side for impact:

“a $5 fee”

“a small $5 fee”

Has the word “small” ever felt so big? A 20% jump in the response rate by adding a single word ... the devil really is in the details!

When you can accurately identify additional charges as small or unimportant, be sure to highlight that they are. Reminding people a charge is small definitely affects their perception of it.

Appeal to utility over pleasure

In an additional CMU study, researchers tested frugal spenders’ reactions to paying for a $100 back massage.

They framed the offer in both a utilitarian way (“it can relieve back pain”) as well as with hedonic terms (“it’s a pleasurable and relaxing experience”).

Although the “tightwad” group was 26% less likely to be persuaded by the hedonic message, they only lagged by 9% when it came to the message promoting utility — impressive, considering the offering is a luxury purchase for pretty much everyone except those with true back problems.

While many products combine both of these messages in their selling, be sure to emphasize utility when selling everything but luxury items (where pleasure is the main goal), and especially when selling to more frugal customers.

It’s either free or it isn’t

In Predictably Irrational, Dan Ariely showcases the importance of “free” in respect to things that are almost-free.

Amazon learned this important distinction when they launched a new “free shipping” promotion with the purchase of every second book. When looking at sales, marketers found that every country except France showed a big jump thanks to the new offer.

What’s the deal with the French?

As it turns out, nothing: Amazon had in fact made the offer in France to include a menial charge of only a single franc (~20 cents). In essence, this is really the same offer, as 20 cents is essentially nothing when compared to buying a book of $10 or more, especially when it’s just for shipping.

The results were clear: Performance didn’t change when this offer went live, but when things were switched over to “free” shipping in the subsequent weeks, sales improved to levels seen in all other countries.

When selling to customers, consider if it’s worth adding on additional minor charges. What if, instead, you incorporated these costs into your overall offering?At this point, these extras would be seen as free and wouldn’t create another decision point, easing the process for especially conservative buyers.

When you shouldn’t even bother...

Although it pains our customer-loving selves to say this, there is a certain kind of customer you don’t want to bother with.

In an paper titled “The Mismanagement of Customer Loyalty,” HBR calls these customers “barnacle” customers because they:

... do not generate satisfactory returns on investments made in account maintenance and marketing because the size and volume of their transactions are too low. Like barnacles on the hull of a cargo, they only create additional drag.

Ouch!

(These customers are labeled as such based on their spending habits — it’s not an assumption of their overall character!)

While it might seem strange to want to avoid customers of any variety, here’s the cold hard truth: You are doing both you and this sort of customer a favor.

You avoid customers who aren’t truly interested in your offering, and you also help these customers who wouldn’t truly fall in love with your product anyway.

You can do this by positioning your brand so that it outright favors certain customers over others, and you don’t have to be rude in the process.

We know, for example, that while customer service is important for practically every business, Help Scout is going to be optimal for certain types of businesses. We position our content around this positioning so that anyone who visits our blog gets what we’re all about right away. Check out a few of these posts:

You’ll notice a trend in all of these articles. There is an emphasis on putting customers first, and building and growing customer-centric businesses. They’re designed to be most interesting to one group of people: the typical Help Scout customer.

Your brand’s positioning should actively avoid customers who aren’t suitable for your offering.

This way, you won’t have to play the price game with customers who aren’t truly interested in your product (leaving you time to focus on the customers who are), and these customers won’t be wasting their time by trying an offering that isn’t for them.

Don’t be scared to strongly position your business. Define your offering, describe your ideal customers, and be sure to outline just who isn’t a good fit for your business, you’ll be doing everybody a favor in the long run.