A habit, wrote B.R. Andrews for The American Journal of Psychology waaay back in 1903, “is a more or less fixed way of thinking, willing, or feeling acquired through previous repetition of a mental experience.”

What we’ve learned more recently is that habits — whether personal, organizational, or societal — are a subconscious loop. Acting “without thinking,” writes psychologist Jeremy Dean in Making Habits, Breaking Habits, “or ‘automaticity,’ is a central component of a habit.”

All of us can admit to a poor work habit that holds us back. Maybe we’re always interrupting people, or we’re chronically late to meetings, or we’ve got an excuse for everything that goes awry.

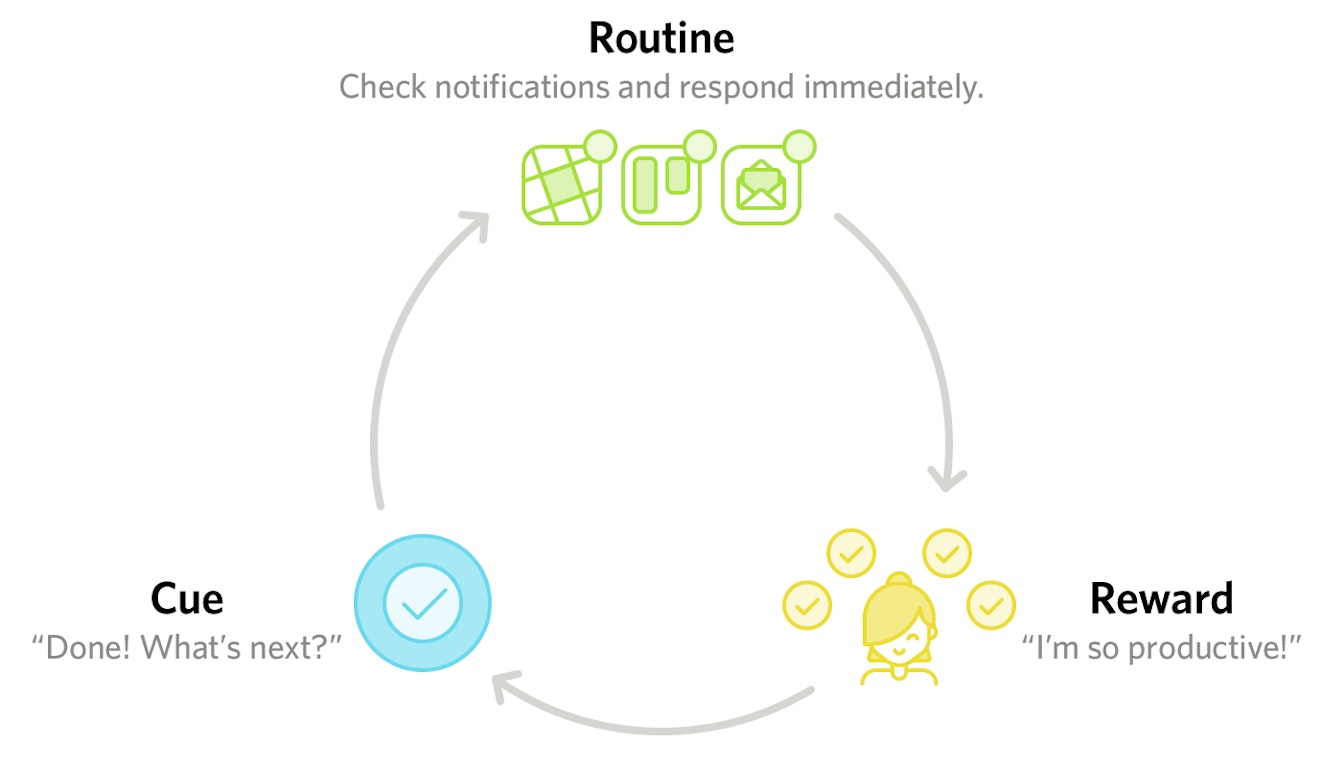

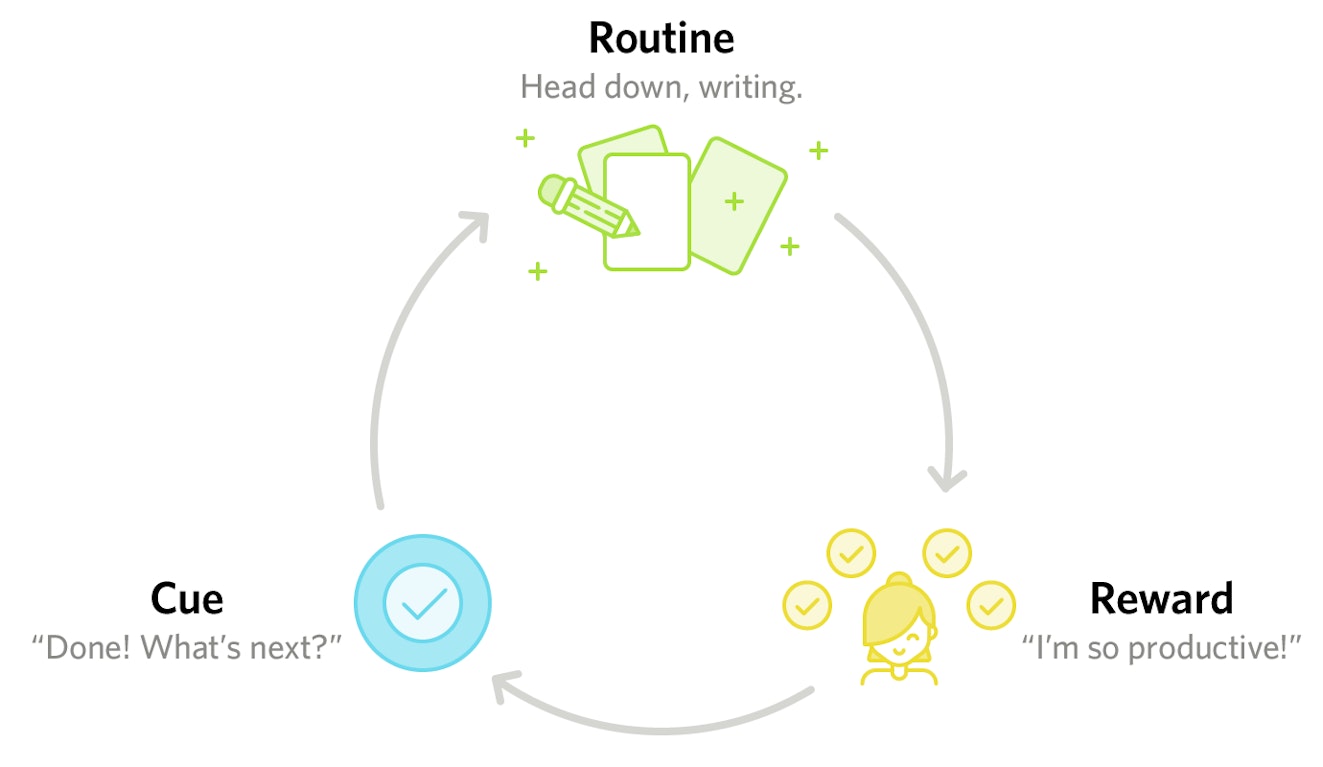

These subconscious loops, as Charles Duhigg notes in his bestseller The Power of Habit, more or less follow the same pattern: a cue (or “trigger”) that sets your brain on autopilot, the routine you act out, and the reward you get from doing it, which reinforces acting upon the cue the next time it appears.

My own worst work habit, for example, is ping-ponging between email, Slack, Trello and Twitter notifications while heavier and higher-priority tasks (like, oh I dunno, writing this article) get put off.

The cue is finishing one task — like replying to an email — which signals a desire to move on to the next thing (“what now?”). My routine is to check all my applications and immediately address whatever new stuff is waiting for me there — often, a Slack message or another email. The reward is the satisfaction I get from feeling productive by checking off a number of tasks. The problem, of course, is that I haven’t tackled my priorities, and my to-do list hasn’t changed at all.

“Over time,” Duhigg writes, “this loop — cue, routine, reward; cue, routine, reward — becomes more and more automatic. The cue and reward become intertwined until a powerful sense of anticipation and craving emerges. Eventually … a habit is born.”

Despite my best intentions at the outset of each day, the dopamine rush that comes from checking my notifications is difficult to ignore. It seems no number of well-meaning articles I read about how “context-switching kills productivity!” can counteract the neurological trench this habit has carved deep into my basal ganglia.

No doubt you’ve felt captive to some habit that’s holding you back, too. So how do you fix it?

How to break your bad habits

Get curious in the moment

The first step in breaking any bad habit is awareness. When you’re mindful in moments subject to automation, the follow-through is no longer a foregone conclusion. The more aware we are of what causes our cues, routines and rewards, the less power our habits hold over us.

In a TED talk about bringing curiosity to our habits, psychiatrist Judson Brewer argues we can start to change our habits by being mindful in the moments during which we’re acting out the habit loop.

“What if instead of fighting our brains,” he asks, “ … we just got really curious about what was happening in our momentary experience?” He gives the example of smokers who bring mindfulness to the act of smoking, which ultimately causes them to become disenchanted with the behavior — a technique Brewer claims is twice as effective as the current “gold standard therapy at helping people quit smoking.”

I gave curiosity a shot. Once I felt the familiar cue to check off a task and subsequent compulsion to see who retweeted me, I slowed down and asked myself what was really going on. There was the notification-checking dopamine, for sure, and a healthy dose of FOMO, too. But the primary reason I thoughtlessly pinball from application to application? I’m tricking myself into believing I’m being productive.

“(A) lot of the busyness that goes on during workdays gives us a false sense of productivity that’s dishonest to indulge,” writes Laura Vanderkam in 168 Hours. “Doing a lot does not mean you’re doing anything important.” Playing whack-a-mole with my notifications is far from the best use of my time, but it sure makes me feel like I’m busy and important and Taking Care of Business.

Disenchanting indeed. Being aware of what I get out of this habit — a false sense of productivity — was a powerful first step in changing it. But I needed a replacement routine.

Transforming bad habits by replacing routines

While you can’t truly eradicate a habit, you can reform it by replacing the routine that occurs between the cue and the reward. “That’s the rule,” Duhigg writes. “If you use the same cue, and provide the same reward, you can shift the routine and change the habit. Almost any behavior can be transformed if the cue and the reward stay the same.” What a liberating formula! (At least one company hopes to capitalize on this insight by selling a device that replaces the “routine” segment of the habit loop with an electric shock.)

Now when I complete one to-do and the “what’s next?” cue arrives, my replacement routine is to alert my team I’m going “heads down” and close everything but the tools I need for the task at hand. The reward is the same: the satisfaction of feeling productive. Except now, it’s actual productivity, versus laziness dressed up in a convincing Halloween costume.

The hidden benefits of habit reform

The remarkable ancillary benefit of kicking just one bad habit is that the positive change spills over into other parts of our lives. While we don’t know exactly why this happens, we at least know that it does and that the principle applies not only to our individual lives but to societies and organizations. When Paul O’Neill took the helm of the flailing aluminum giant Alcoa, for example, he chose to hone in on worker safety. The focus on reforming that one keystone habit, Duhigg argues, was what turned Alcoa around and into one of the best performing stocks in the Dow Jones index.

What might happen if you chose one bad habit and spent a week or so getting curious about it? Once you identify the cue, routine and reward, can you find a new behavior to insert in the “routine” slot? What might happen at your company if you transformed one keystone habit — say, the way meetings are run or how new employees are onboarded? How might those initial shifts set off positive chain reactions?

“Once you understand that habits can change,” Duhigg writes, “you have the freedom — and the responsibility — to remake them. Once you understand that habits can be rebuilt, the power of habit becomes easier to grasp, and the only option left is to get to work.”